Creation of Dual Power Centres and concerns about National Security – The 19th Amendment

by M.L.WICKRAMASINGHE

The amending of Constitutions is a rare and serious activity. For example, the Constitution of the United States of America has had only 27 amendments for about 225 years. In Sri Lanka the 1978 Constitution has had 18 Amendments already; the 19th has been Gazetted as a Bill. It would augur well for the country’s future if more Sri Lankan citizens, will offer constructive ideas to further refine and improve the 19th Amendment, and its framers would accept useful feedback with an open mind. People’s participation is especially important for it is they who would either enjoy the impact of a good Constitution or suffer the consequences of ill conceived amendments.

I am not a legal or constitutional expert; but considered it a national duty to review the Gazetted Bill based on knowledge gained by reading as well as learning from experiences while working in a number of countries with different constitutional and political systems. It is the thesis of this article that the draft 19th amendment would lead to the creation of ‘dual centres of power’ within the executive, and hence may affect maintenance of national security in the country.

Dr. N.M. Perera who is no more with us, but who is still acknowledged as an expert on Constitutions, commenting on the attempt made by the Government of Mr. J.R. Jayewardene to move a second Amendment to the 1972 Constitution, (before finally dropping it to introduce a new Constitution in 1978,) referred to the unhindered functioning of a Constitution as a key criteria for its acceptance by the people. He wrote – “An amendment to a Constitution should receive wide discussion and deep consideration by all sections of the people.……….A Constitution must evoke the unstinted loyalty of the people by its acceptability and its capacity to respond to the needs of the people. It is not the letter of the law of the Constitution that can earn the respect and evoke this loyalty. It’s the spirit that animates its effective functioning.” He was also of view that amendments to Constitutions should not be rushed through as it results in inclusion of loose, imprecise and or conflicting Articles and clauses which only benefit the legal community, as they would be called upon to sort out the ensuing ambiguities. (Ref: N.M. Perera: Critical Analysis of the New Constitution of the Sri Lanka Government promulgated on 31.08.1978. Reprint of Original by Dr.N.M.Perera Trust, Sept. 1991)

According to my understanding, the main purpose of a democratic Constitution is to establish systems, processes and guidelines to balance powers of the three key branches of government, namely, the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. The legislature creates laws; the executive administers laws; the judiciary enforces laws. Too much power in one branch of the government could adversely affect people’s freedom. Although the powers of the three branches should be delineated and mechanisms designed to keep the powers in some kind of equilibrium, it is also vital to ensure that mechanisms are in place to enable the three organs to also work in co-operation, if the business of governing or running a country is to proceed smoothly and efficiently.

Everyone accepts that a Constitution is primarily a legal document as it is the supreme law of the country; but very few give thought to the fact that its contents are influenced by a country’s social, cultural, and economic situation; fundamental political philosophy; national security situation including external and internal threats; human rights and freedoms enjoyed by the citizens; inclusiveness and social cohesion etc. Amendments to Constitutions should be based on a current situation analysis linked to a future projection, so that the amendments would help a country to achieve a better future for its people in the long-term, while removing weaknesses in the existing Constitution, and strengthening positive aspects of governance.

The Constitution as the supreme law of the country should also be neutral to needs and wants of current and potential future leaders, current and future political power configurations, as well as overseas lobbyists with extremist ideology. Hence when framing amendments the Framers may not think, -OK, Person ‘A’, or the current power configuration X, is acceptable so we will amend some constitutional parameters for the time being and watch the developments. Constitutions are for the long haul. The framers of amendments should have a long-term view of the country, and have as their goals, the promotion of good and effective governance, well being of citizens, and national security. The short term political perspectives should be kept out of the equation, although there could be pressure to take that line.

Thus, it is vital to move the current public debate on the 19th Amendment away from concepts of good and bad persons, ideal legalistic models, and political party motivations. The debate should be moved to a higher ground so that many people are encouraged to study and offer ideas on issues such as the following: the effectiveness of separation of powers; advantages and disadvantages of an executive presidential system vis-a- vis a parliamentary (executive) system; abolishing the executive presidency vs reducing its power, and pitfalls to watch for, in such a venture; the constitutional experiences of various other countries in using the two systems; reviewing national experiences in the use of the proportional representation and preferential system of voting; mechanism for promoting good governance; and last but not least the Constitutional powers endowed to the executive authority to protect national security and territorial integrity of the country.

An analysis of the draft 19th amendment shows that it has desirable features, such as the section on access to information commencing with Article 14A; reducing the term of a President to two five year terms, Articles 30(2) and 31 (2); and strengthening independent Commissions (Articles 41B) etc. However, there are substantial gaps and conceptual problems with regard to some of the Articles in chapters VII and VIII. In this analysis I wish to comment on the inherent contradictions of some articles in Chapters VII and VIII, and the possible impact these weaknesses would exert on the national security of the country.

A striking weakness of the draft 19th Amendment (the Bill as published in the government Gazette) is the opening of doors for the creation of two ‘executive centers of power’ within the government. A critical analysis of some of the Articles in the draft Bill reveal the opportunities presented for the subtle generation of dual power-centers leading to possible friction between the President who is the Head of State and Head of the Executive and the Prime Minister who is the Head of the Cabinet. The splitting of the executive authority in the country may lead in the very extreme situations, to episodes of paralysis in governmental decision-making, and or delay in government decision-making. These outcomes could affect the sovereignty of the people and their well being.

The key articles under discussion and analysis are:-

Article 30 (1) ” There shall be a President of the Republic of Sri Lanka, who is the Head of the State, Head of the Executive and of the Government and the Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces”. (The writer has marked some clauses in bold letters to help the readers to focus on key issues under discussion.)

Article 33A “The President shall be responsible to Parliament for the due exercise, performance and discharge of his or her powers, duties and functions under the Constitution and any written law, including the law for the time being relating to public security”

Article 42(1) “There shall be a Cabinet of Ministers charged with the direction and control of the Government of the republic”.

Article 42(3) “The Prime Minister shall be the Head of the Cabinet of Ministers”.

Articles 43 (3) “The Prime Minister may at any time change the assignment of the subjects and functions and recommend to the President changes in the composition of the Cabinet of Ministers”.

Article 44 (5) “At the request of the Prime Minister any Minister of the Cabinet of Ministers, may by notification published in the Gazette, delegate to any Minister who is not a member of the Cabinet of Ministers any power or duty conferred or imposed on him or her by any written law…………………”

The President although anointed as the Head of the State, the Executive and of the Government (as per Article 30(1)) is check-mated brilliantly by the provisions of Articles 42 to 44. The Prime Minister (PM) according to powers vested in him or her by virtue of Article 42(3) is the Head of the Cabinet of Ministers. It is this Cabinet of Ministers (headed by the Prime Minister,) that is charged with the direction and control of the Government of the Republic as per Article 42(1). The PM is also given powers to change any Minister in the Cabinet, and also change the subjects given to Ministers as per Article 42(3). The PM can on his own request a Cabinet Minister to hand over part of his assignment to a Member of Parliament who is not in the Cabinet by virtue of powers vested in him by Article 44(5).

Therefore, the President appear to have no role in directing the Cabinet of Ministers according to Articles 42 (3), 43 (3) and 44(5) although he is designated as the Head of the Government in Article 30(1). Conversely it is mentioned that the President, has to be responsible to the Parliament in discharge of all his duties, including public security. But how the President is expected to achieve this or the mechanism through which the president becomes responsible to the Parliament is left unsaid, leading to ambiguity and guess-work. Is the Prime Minister the medium through which the President become responsible to the Parliament? The silence appears to be deafening. Whatever it is, the hidden duality is fairly obvious to the critical reader, and therefore would need to be sorted out in the interest of effective governance.

Even with regard to the composition of the Constitutional Council (CC), the President’s authority to nominate members has been downgraded. Please read Article 41A (1), clauses (a) to (f) which cover the nomination of the CC. Out of a total of 10 members recommended to be appointed to the CC, the President who is elected by the direct vote of the people is authorized to nominate only one member. He does not, (in theory as per the relevant Articles) even have the power to raise an objection with regard to the suitability of any of the balance five non-ex-officio members proposed to be nominated as per Article 41 (6). On the other hand, the Prime Minister with the Leader of the Opposition together, can nominate five members in addition to both of them becoming ex-officio members in the CC. That is between the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition, they can hypothetically control 07 members of the Constitutional Council out of a total of 10 members. At every opportune stage, the draft 19th amendment seeks to constrain the power of the President, despite the fact that the President exercises the sovereignty of the people through direct franchise, in all of the nine Provinces in Sri Lanka.

The draft 19th amendment either wittingly or unwittingly weakens the executive authority of the country by creating a mechanism for dual control of executive authority. Some of the powers (i.e. Head of Executive and Head of Government) vested in the Office of the President by virtue of Article 30(1) appears to be placed under challenge by powers vested in the Office of the Prime Minister via Articles 42(1) and 42(3). The powers vested in the office of Prime Minister by virtue of Article 42(3) to be the Head of the Cabinet of Ministers and by virtue of Article 42 (1) to direct and control the Government through the Cabinet of Ministers appear to be challenged by some phrases in Article 30 (1). This weakens the Sri Lankan State at a time when the State of Sri Lanka needs to stay strong.

There can certainly be no reason for any person to object to the reduction of the power of the President, if the purpose of the exercise is to establish requisite checks and balances among the three main branches of the government, the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary, without depleting executive power of the Sri Lankan State. However, in my humble opinion, the effect of the above amendments contained in chapters VII and VIII of the 19th amendment Bill would lead to truncating of the powers of the executive. Rather than attempting to balance the power between the executive and the legislature, the practical implications of the draft 19th amendment is the depletion of the power of the executive of the State of Sri Lanka. It is akin to the rudder of the Ship of State being put under the control of two captains.

The result is that the executive decision-making of the State may be deadlocked, or at the very least be delayed. In such a scenario the biggest concern is on defense, national security and territorial integrity of the country. For the defense of a country, executive decision-making must be untrammeled and rapid. Any dilly-dallying on the part of the executive, due to differences of opinion between the two ‘created power centers’ of the Prime Minister and the President, would be detrimental. A country at all times should be prepared to defend itself, whether there are any threat on the horizon or not. That is what India, the USA, China, or Japan would do, as well as Nepal or the Maldives. But in Sri Lanka, the concept of ‘dual- executive power’ is sought to be introduced, through the draft 19th amendment at a time of transition from conflict to peace and reconciliation, and when the concept of separatism to win rights has still not been totally disavowed by many key stakeholders in and outside the country.

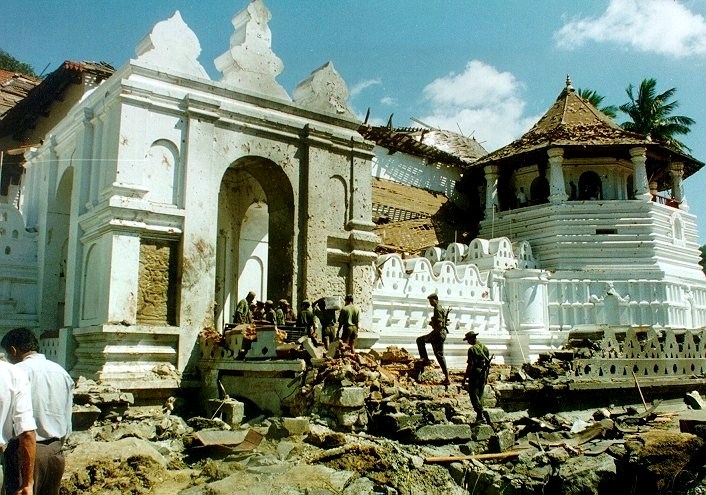

The country is still in a stage of consolidating the peace gained in 2009, and promoting national reconciliation. The new government is beginning to take more measured steps towards promoting greater reconciliation. Simultaneously, a gradual increase of political belligerence is being noticed in the northern provincial council (NPC).This, to say the least, is unhelpful. It appears that many Sri Lankans including fair thinking Tamil citizens are perturbed over the politically belligerent line taken by the NPC under its Chief Minister (CM). Some Sri Lankans do believe that these unpalatable posturing mark the beginning of a cycle of belligerent demands for greater devolution of power to the north. The examples that gives rise to such perceptions are: – the ‘genocide’ resolution passed by the NPC alleging that all Sinhala governments since 1948 engaged in genocide against the Tamils; the CM’s statements made some time back to the effect that they need to look for a more “dynamic” solution to the question of power devolution; and also the oft-bandied statements about a `beyond the 13th amendment’ solution. Even some of the so-called moderates within the TNA have mentioned that the 13th Amendment would not be a solution. These developments indicate that the situation is still fluid in this regard, and the country should not put its guard down.

Mr. Neville Ladduwahetty in an insightful comparison of the Indian Constitution with the 13th Amendment of the Sri Lankan Constitution in an article published in the Island newspaper of 28 March, 2015, showed how the Sri Lankan 13th Amendment gives identical power to the Provincial Councils in Sri Lanka as the Indian Constitution does to its State governments, although the Sri Lankan provinces are much smaller than the Indian states. Therefore, the snowballing of statements on ‘the need to go beyond the 13th Amendment’, or to look for a more ‘dynamic’ solution’ is worrying.

In classical theory, the move to promote national reconciliation and a move to provide greater devolution of power could be considered to be inter-dependent and mutually supportive. However, there is tension between the two in that any undue weight placed on increased devolution of power could unleash centripetal forces which a small Sri Lanka placed at fishing boat distance from Tamil Nadu would find hard put to counter. The former statement is the so-called theory. The latter statement is the practical and locality- specific situation given, the geographic location of Sri Lanka. The latter situation mandates a tight balance between the two concepts. And as Mr. Laduawahetty has clearly shown in the above article in the Island, the Indian Constitution has stipulated the absolute outer limits of devolution. Sri Lanka can opt to select the degree of devolution from within the Indian model, which is suitable for the country taking into consideration the transitional conditions as it move from post-conflict situation to consolidating peace and reconciliation. Mr. K. Godage, a respected foreign service officer of Sri Lanka, in an article titled ‘Devolution in India and Sri Lanka’ published in the Island of 01 April 2015, while commending Mr. Ladduwahetty for the comparison, informs us of possible options: “Malaysia has almost 150,00sq.km. comprising 11 States ….. In that country police are a central function”. The degree of smoothness of developing peace and reconciliation would generally match people’s perceptions of assurance of national security and territorial integrity. This is one of the fundamental reasons why the Sri Lankan Constitution should continue to endow as well as repose legally ‘unchallengeable’ executive authority within the central government of Sri Lanka for defense, national security, and protection of her territorial integrity.

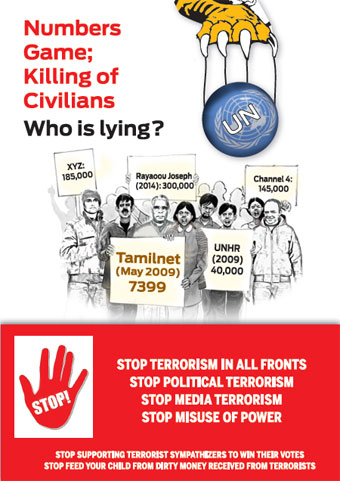

This view by no means vitiate the central understanding of the vast majority of Lankans that the new government should wholeheartedly support all measures to enhance the quality of life, the livelihoods, and the basic human rights of all Lankans, while making an extra-effort to enable Tamil people to enjoy these needs and rights as they suffered substantially due to the terrorist war inflicted upon the country by LTTE. All citizens of this country want genuine grievances of the people of the north and east resolved as stated in the Presidential Commissions on Lessons Learned and Reconciliation Report. The previous administration had begun a substantial amount of work in this regard; the current administration has begun to accelerate and enhance the process. While all this is being done the vast majority of Lankans also believe that the country and the people should not provide even a smallest window of opportunity for any kind of terrorism or separatist doctrine to arise gain. Some of them also seem to be fighting an internal battle within their conscience about the nagging fears they have of the real (hidden) intensions of some of the northern and eastern politicians, the western international community, the hard-core LTTE diaspora, and of UNHCHR’s stance on Sri Lanka. This should not be dismissed as mere ‘sloganeering’. These are genuine dilemmas confronting the majority of our people.

The Constitution of the United States of America was born due to the strong-felt needs of citizens, some State leaders as well as the majority of National leaders to strengthen the power of the central government in the aftermath of the Independence war in order to protect the country from any threat of disintegration or break-up. The 19th amendment as currently drafted, perhaps unknowingly, is paving the way for a weakening of the executive authority of the State of Sri Lanka by attempting to create dual centers of executive authority. It may be wise to take a leaf out of USA’s book and re-fashion the draft 19th amendment to ensure that the executive power and authority of the State of Sri Lanka is not divided nor diluted.

It is hoped that views such as these are also considered in finalizing the 19th amendment.

859 Viewers