Bishop Tutu misled

In an ironic twist, Bishop Desmond Tutu had signed a petition calling on the UNHRC to appoint a commission of inquiry against Sri Lanka just when the Sri Lankan government was examining how the good bishop brought about reconciliation in South Africa which was certainly not through commissions of inquiry. Bishop Tutu’s co-signatories to the petition

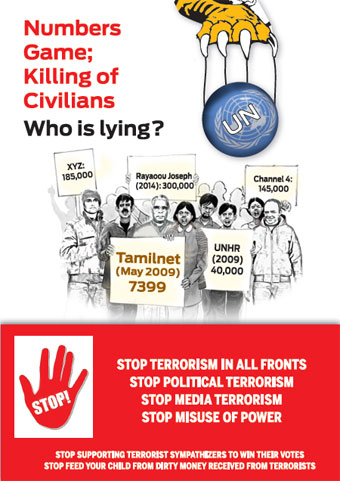

asking that a commission of inquiry on Sri Lanka be appointed were the likes of Yasmin Sooka (of Darusman report fame) R.Sampanthan, Bishop Rayappu Joseph, C.V. Wigneswaran et al which explains many things. The bishop appears to be keeping company only with one side of the Sri Lankan conflict and he appears to know only what that side tells him. The South African government which has heard both sides, firmly took the side of the SL government. None of this however should prejudice Sri Lankans against Bishop Tutu because his contribution to the world far outweighs any statement he may sign about Sri Lanka.

The manner in which Bishop Tutu implemented the provisions of South Africa’s Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act No. 34 of 1995 as the Chairperson of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission will remain an inspiration to all nations recovering from internal conflicts. At the very core of the South African truth and reconciliation process lie the indemnity law that applied equally to both warring factions. The good bishop implemented this indemnity law with a determination and clarity of purpose one would expect of a consummate politician, not a priest. He was at pains to tell the world that the South African amnesty process was unique in that it provided not for blanket amnesty but for a conditional amnesty, requiring that offences be publicly disclosed before amnesty could be granted. Though he said this, in reality, the bishop knew and he said so in his report on the TRC, that it was only those who were already on the dock, or thought their doings would one day come to light that came before the TRC and asked for an amnesty. He knew that what he was doing was not so much a search for the truth as a sweeping of it under the carpet. It was an uphill battle all the way for the bishop to justify the amnesties he was handing out.

He wrote in his TRC report: “There were those who believed that we should follow the post World War II example of putting those guilty of gross violations of human rights on trial as the allies did at Nuremberg. In South Africa, where we had a military stalemate, that was clearly an impossible option. Neither side in the struggle (the state nor the liberation movements) had defeated the other and hence nobody was in a position to enforce so-called victor’s justice. However, there were even more compelling reasons for avoiding the Nuremberg option. There is no doubt that members of the security establishment would have scuppered the negotiated settlement had they thought they were going to run the gauntlet of trials for their involvement in past violations. It is certain that we would not, in such circumstances, have experienced a reasonably peaceful transition from repression to democracy. We need to bear this in mind when we criticize the amnesty provisions in the Commission’s founding Act. We have the luxury of being able to complain

because we are now reaping the benefits of a stable and democratic dispensation. Had the miracle of the negotiated settlement not occurred, we would have been overwhelmed by the bloodbath that virtually everyone predicted as the inevitable ending for South Africa. Another reason why Nuremberg was not a viable option was because our country simply could not afford the resources in time, money and personnel that we would have had to invest in such an operation. Judging from what happened in the De Kock and so-called Malan trials, the route of trials would have

stretched an already hard-pressed judicial system beyond reasonable limits. It would also have been counterproductive to devote years to hearing about events that, by their nature, arouse very strong feelings. It would have rocked the boat massively and for too long.”

When Bishop Tutu signed that petition to the UNHRC asking for a commission of inquiry on Sri Lanka, it is clear that he has been misled by the Tamils he keeps company with. He does not seem t be aware, that the Sri Lankan government forces won a comprehensive victory over the Tamil terrorists, yet they did not impose a victor’s justice on the vanquished terrorists. Most of these terrorists have been rehabilitated and granted amnesties. While nobody opposes the blanket amnesty granted to the terrorists, everybody seems to be opposed to a similar amnesty being granted to the victor. In Bishop Tutu’s case, he was handing out amnesties to participants in a conflict that had not been won or lost but had been resolved on the basis of an agreement. He would be shocked to hear that the while the Sri Lankan government has won the war on terror and given the vanquished a blanket amnesty, the government has done nothing yet to grant a similar amnesty to the victor!

When the Sri Lankan government finally gets round declaring immunity from prosecution for the victor, there is an important matter that Bishop Tutu pointed out in his TRC report that they should take note of. When Bishop Tutu was handing out amnesties in South Africa, applications for amnesty were received from persons in leadership positions in

various political groupings (especially the African National Congress) who accepted collective responsibility for human rights violations. Though such people applied for amnesty, they were not able to reveal a specific offence they had committed and were therefore not eligible for an amnesty according to the mandate of the TRC. The expedient adopted in such cases was to declare that none of the applicants had committed any offence! Bishop Tutu was so much in favour of granting indemnity to such individuals that he pointed out in his TRC report that in the latter instance where some individuals could not be granted amnesties because they could not disclose a specific crime they had committed, that it would be in the interests of justice to clarify ‘the mistaken public impression’ that these applicants are liable for prosecution because they had not been granted amnesties. The bishop’s view obviously was that such individuals are not liable for prosecution even though they had technically not been granted an amnesty. Bishop Tutu’ observations with regard to such grey areas should be taken note of by the Sri Lankan government if they are thinking of setting up a South Africa style Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The powers of the Amnesty Committee in Sri Lanka should be wide enough to deal with instances where an applicant may not be able to specify a particular act for which he was seeking an amnesty.

783 Viewers