Revisiting Sri Lanka’s foreign policy

(Courtesy of The Island)

The perception both nationally and internationally is that Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy under the administration of former President Rajapaksa was China-centric. By way of a course correction, President Sirisena’s administration is attempting to re-establish lost ground with India and the West. As part of this new pivot to India and the West, attempts are being made by the new administration to diplomatically distance itself from China starting with a review of the projects that are being financed and executed by China. The most prominent of these is the Port City project originally proposed by a Singaporean company CESMA in 1998 at the initiative of the Government of Singapore (The Island, January 22, 2015).

The prospect for post-conflict Sri Lanka was the urgent need for economic development. While acknowledging that the preferred option for economic development is Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) it also has to be acknowledged that without basic infrastructure it is not possible to attract FDIs. Therefore, the focus was infrastructure development in the form of Power Generation, Transportation and Harbours. Hence, the need to start the long delayed Norochchalai and Upper Kothmale projects for power; Airports, Expressways, Road and Rail development to facilitate transportation; and expansion of Colombo South Harbour and Hambantota Harbour being the key development related infrastructure projects.

SOURCES of FUNDING

Dr. Sarath Amunugama informed Parliament that the four usual methods for financing major projects were: (1) via Multilateral Development Agencies such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB); (2) via bilateral Development Agencies such as JICA of Japan, EDCF of Korea, SDF of Saudi Arabia, OPEC; KfW of Germany; (3) Export Import Banks – EXIM of India, China, Korea etc.; (4) Foreign Currency dominated Sovereign International Bonds (Hansard, December 8, 2012, p. 3164, 3165).

Since post-conflict Sri Lanka had a per capita GDP of $2000+ in 2009 and therefore reached the status of a middle income country, the only sources of funding available was from the latter three categories. According to the Hansard cited above: “Each foreign loan is examined by the Monetary Board of the Central Bank… All loan agreements are approved by the Attorney-General confirming, inter alia, compliance with the laws of Sri Lanka (and) …are executed after having obtained the approval of the Cabinet of Ministers and … special authorization of the President”.

FUNDING PROJECTS

The economic status of post-conflict Sri Lanka was such that though ADB funding was available for some projects, the majority of the projects had to be funded either through bilateral Development Agencies or Export Import Banks. However, it must be recognized that even though the terms for funding of projects through the ADB appear at first glance to be attractive, the time consuming procedures involved make the gloss on the terms for funding fade when lost opportunity costs are factored in. Therefore, under the circumstances Sri Lanka is currently in, it is more likely that the sources for funding infrastructure projects are bilateral Development Agencies and Export Import Banks of countries.

From a Foreign Policy perspective, funds available from Development Agencies in the West are few and far between. The majority of them are from the East. The latter not only have the funds but also the capabilities to design and construct major infrastructure projects with China undoubtedly in the forefront in this regard. As for India, though it has the capabilities to finance, design and construct major infrastructure projects, the Central Government under the Congress Party could not engage in Sri Lanka due to Tamil Nadu’s objections to anything and everything connected with Sri Lanka and the Indian Central Government’s dependence on Tamil Nadu for its very survival.

Although the current government of Prime Minister Modi is free of such constraints, the bottle necks associated with the Sampur Power Plant demonstrate the lost opportunity costs involved when dealing with India. Furthermore, this project is not funded through an Indian Development Agency. Instead, it is a Joint venture between the CEB of Sri Lanka and the NTPC (Ltd) of National Thermal Power Corporation Ltd. (NTPC) of India India. Therefore, to focus on interest rates and payback periods without factoring in lost opportunity costs reflects the inability of commentators to see the larger aspect of cost to the country.

Another instance of lost opportunity concerns the construction of the Hambantota Harbour. The construction of the Hambantota Harbour was first offered to the United States way before the Rajapaksa administration. Having failed to engage the US, the offer was then made to India. This, too, failed, the main reason being that India’s private sector was not interested and the Central Government under the Congress Party was reluctant to undertake any development projects in Sri Lanka because of the antipathy of Tamil Nadu; a factor that has dominated India’s Foreign Policy towards Sri Lanka. It was the merging of Sri Lanka’s interests with those of China that caused the project to finally take off.

FOREIGN POLICY DIMENSION OF DEVELOPMENT

Post-conflict Sri Lanka’s engagement with China was pure pragmatism. It had little to do with turning away from India or the West. Had Sri Lanka not taken the risk to turn to China and other countries in the East such as Japan and Korea for the sake of good relations with India or the West, there would have been a serious setback to Sri Lanka’s economic advancement. With the conclusion of the conflict an opportunity was presented for rapid economic development starting with major infrastructure projects without which Foreign Direct Investment could not be attracted. In their haste to achieve results some of the terms negotiated may perhaps appear excessive to those with a tunnel vision. But, they should not be looked at in isolation. Instead, they should be seen from a broader overall economic perspective in terms of benefits to the society and country as a whole.

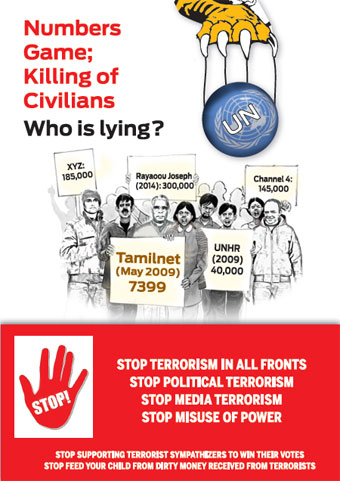

Perhaps, Sri Lanka could be faulted for not mending fences with India and the West while pursuing it economic objectives with China. Sri Lanka could have engaged with the West by carrying out an internal investigation into conflict related accountability issues. Sri Lanka was reluctant to engage in such an exercise because of an interpretation that the conflict was between a state and a non-state actor, thereby placing greater responsibility for accountability on the state and hardly any on the non-state actor; the LTTE, despite having the land, sea and rudimentary air capabilities of a military establishment. On the other hand, had Sri Lanka taken a position that the conflict was an “Armed Conflict” where both parties were equally accountable, as reflected in the positions taken by the West as well as in UN Resolutions, and actions judged in terms of Rules of War, issues could have been addressed in a more clear-cut manner with positive results in its relations with the West.

Behind this veil of engaging in tasks to rebalance Sri Lanka’s relations with the West and India, the stark reality is that both the West and to a greater extent India are disturbed by the extent of China’s involvement with Sri Lanka; the largest engagement being with the Port City Project. The perception that the presence of China needs to be reduced in order to “eliminate the element of corruption” was expressed during the course of an interview with the Daily Mirror by the new Finance Minister Ravi Karunanayake when he stated: “The economic presence of China needs to be reduced to eliminate the element of corruption…. If China can give us loans at 0.5 percent, we would love to take it. But, not the 8 percent interest loans; of which 4-5 percent went into the pockets of certain individuals and two or three family members. That is not allowed” (January 24, 2015).

Considering the multi-stage procedures involved in negotiating loans with Government- owned Development Agencies, such irresponsible statements are bound to have a negative effect on Sri Lanka’s relations with China. Furthermore, how Sri Lanka proposes to ‘reduce’ China’s economic presence in Sri Lanka would be closely watched by all concerned parties. If Sri Lanka succeeds in this endeavour, it would put a dent in the development processes because takers with comparable capabilities do not exist.

CONCLUSION

Although the West, in particular the US, and India assisted Sri Lanka during the conflict, post-conflict Sri Lanka came under pressure from both quarters for urgent resolution of accountability and political issues in the name of human rights and reconciliation. On the other hand, Sri Lanka’s immediate priority was to focus on development. To post-conflict Sri Lanka China represented a one- stop shop to undertake its development needs.

If not for Norochcholai there would be power cuts today. If not for the roads, railways and airports, Sri Lanka would not be able to meet tourist demands, facilitate commerce and people to people contact. If not for the expansion of Colombo Harbour, Sri Lanka would not have the deepest harbor in South Asia with the capacity for relay cargo handling. In short, these infrastructure developments have contributed considerably to the creation of an environment for Foreign Direct Investment to follow.

China for its part saw the needs of Sri Lanka meshing with its own needs and the role Sri Lanka could play due to its strategic location in China’s quest for global economic expansion. Therefore, the relationship between Sri Lanka and China was driven by the pragmatic interests of both countries. Consequently, it was not a case of Sri Lanka tilting towards China; both countries were leaning towards each other for mutual benefit. On the other hand, India was prevented from freely exercising its options because of Tamil Nadu and its influence in the Congress Party. And the West could not participate either because of its own preoccupation with the fallout from the 2008 economic catastrophe.

There is no denying that the West and India are concerned with the extent of China’s presence in Sri Lanka, more for the geostrategic and security implications than for economic impact. This could be because of the tendency of the current Modi administration to perceive issues from a traditional security perspective rather than from threats to security from political developments. It is not the presence of China that is a threat to India’s security and territorial integrity but the territorial unraveling of Sri Lanka through devolution to the provinces.This fact was acknowledged by Mr. Krishna, one of India’s former Foreign Ministers, when he commented that the security and territorial integrity of India depends on the security and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka. Therefore, India should be much more concerned with the trajectory of internal politics in Sri Lanka and less with the presence of China in Sri Lanka.

By Neville Ladduwahetty

927 Viewers