Celebrating Cumaratunga

Had he lived, there is no doubt that Cumaratunga Munidasa would have made a long-lasting and interesting contribution to the language and educational reform debates of the 1940s and 1950s. But this was not meant to be. A contemporary of Martin Wickramasinghe and a near-contemporary of Piyadasa Sirisena and Ananda Coomaraswamy, Cumaratunga passed away prematurely in 1944, right at the cusp of the end of World War II. It was that war which,in a way,contributed to his demise: he succumbed to illness at a time when wartime rationing had restricted access to all sorts of medicine.

At the time of his passing Cumaratunga had been acknowledged as the foremost Sinhala linguist of his day. His conception of what constituted correct grammar and good literature did not always win him friends, but it nevertheless appealed to a people who saw in his efforts at purifying the Sinhala language – and ridding it of the many foreign accretions it had acquired over the centuries – a campaign, as the American scholar Garrett Field puts it, at restoring to it a high place in the pantheon of world languages.

An outlier and a radical, Cumaratunga differed from many of his contemporaries. No one who has read his poems and stories – like most other Sri Lankan children I grew up with Magul Kaema and Kumara Gee – can fail to notice his irreverence for the adult world, his sceptical attitude to things often taken for granted. Deceptively simple as these stories were, they enlivened and, in a way, embodied our childhoods.

Pure Fraternity

Not surprisingly, Cumaratunga’s death immediately sparked a campaign to take forward his work. This was a task left largely to the society he founded, the Hela Havula – translated quixotically by Professor Field as the “Brothers of the Pure Fraternity” – and it was a task its members took on with enthusiasm. A year after his death, the Hela Havula organised an event, one which the Fraternity has been holding ever since without interruption.

Then, in 1987, came his 100th birth anniversary, the centenary. That year the Cumaratunga Munidasa Foundation came into being. Under its first Chairman, Professor Vinnie Vitarana, and its first Secretary, Cumaratunga’s son Punu, the Foundation worked on a series of events which helped revive interest in his work in the country.

2012 became another turning point. That year marked Cumaratunga Munidasa’s 125th birth anniversary. By then Punu Cumaratunga had long passed away and his son, Gevindu, was handling and overseeing matters at the Foundation. Gevindu got around to talking with another official, Tiricunamale Ananda Anunayake Thera. Ananda Thera suggested that the organisation embark on something totally different. After a conversation that lasted for some time, both Ananda Thera and Gevindu hit upon the idea of awarding scholarships for students who had topped the Ordinary Level Sinhala paper. After conferring with several officials, including at the Education Ministry, the Foundation instituted the programme that year. Since then, it has become a pivotal part of the Foundation’s work.

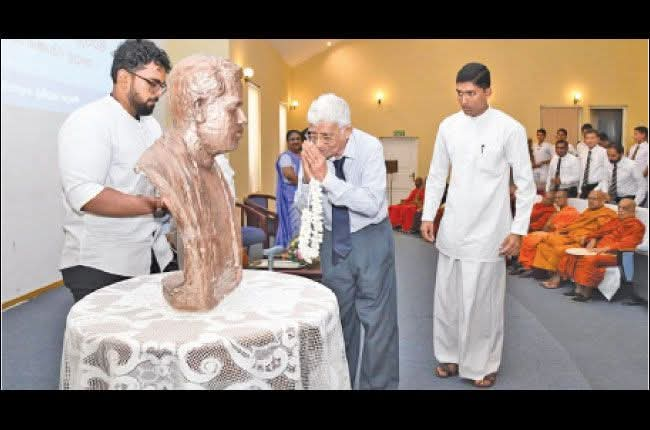

The latest scholarship ceremony took place on 25 July this year – Cumaratunga’s 138th birth anniversary – at the Lighthouse Auditorium and Lawns, Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute, in Colombo. The event was attended by scholars, students, and well-wishers, and the keynote address, the Cumaratunga Munidasa Oration, delivered by Sunil Sarath Perera. The choice of venue was I suppose more than symbolic: special attention was given, early on, to pay homage to its namesake, a man beloved by all and someone who stood for a vision of Sri Lanka which radicals like Cumaratunga would have accorded with.

Linguistic Interest

The winner of the scholarship this year, Sandayuru Aryasinha, is studying biology for his A/Levels at his school. In many ways he epitomises the kind of students who have won the prize over the last few years. When I talked with Gevindu a few weeks back, he observed, quite rightly in my view, that the whole point of the scholarship is not to push its winners to pursue Sinhala at their higher studies. In fact most if not all its past winners have found themselves in diverse, often divergent, fields, including medicine. On the face of it, such fields have little to do with Sinhala. Yet the scholarship, as Gevindu pointed out to me, has helped in keeping their interest in the language alive.

This is important. A language is a crucial marker of a culture, a people, and a way of life. It is also an important part of a country’s diplomacy, something that the Foundation signalled in its choice of location for this year’s ceremony. It is, of course, impossible not to get too prudish about language and culture. There is politics involved in both, and it is difficult to detach it completely from either. Ultimately, however, a language survives through the interest of those who use it, speak it, and write it. Whether an examination is enough to promote that interest is open to debate. Yet in rewarding those who achieve high marks, the Cumaratunga Foundation has made a massive intervention.

Debased Vernaculars

his is all the more laudable given how debased the vernaculars have become in today’s context. Sinhala, in particular, has become a much-maligned victim, partly because of mass media – though it is also mass media that has helped popularise the language among the public. And yet, despite the pessimism this has given rise to, it is wrong to suggest that the young are not interested in the language or in taking it forward. As Gevindu told me when I talked to him, over the last few years students from almost every corner of the country, from the south to the north-western province and beyond, have won the scholarship. Though hardly any of them has chosen Sinhala for higher studies, not a few of them have gone on to write books in Sinhala. This is a trend that the Foundation, despite the stringent financial constraints imposed on it post-2022, has resolved to take forward.

Munidasa Cumaratunga was in many ways a modernist. Mindful of the past, he looked to the future. Though the language forms he championed may not be in popular usage now, several of the terms he, and the Hela Havula, coined are with us today. His death, in that sense, was a blow to his cause. Yet in some form or the other, that cause survives,mainly through the Foundation.As perhaps the most crucial initiative of the Foundation today, the Scholarship has become a lever for the young to carry forward their interest in the mother tongue. Yet it is clear that more needs to be done.

A good starting point, the way I see it, would be the many books that Cumaratunga wrote: books that are hardly well-known among the young, but that would revive interest in the author and in Sinhala language and literature should they be republished. This is a project the Foundation is keen on doing. It is one it should do and see, till the end. If seen through, it would be a worthy counterpoint to the Scholarship.

33 Viewers